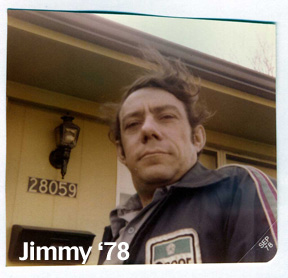

Woodward Ave’s Legend, Jimmy Addison

Written By: Bill Stinson, published with permission.

Bill wrote this story in May of 2006, but it wasn’t until 2007 when I first saw the Silver 1967 (not 68) Plymouth GTX known as the Silver Bullet. The undisputed “King of Woodward Ave” drew a crowd for days at the legengary Woodward Avenue cruise and stirred up quite a controversy when there were two of them! (that’s another story about the Silver Bullet)

Please enjoy this story from a man who was there and knew the owner of the Silver Bullet, Jimmy Addison.

The Passing of a Legend

I first met Jimmy Addison around 1961. The McKay family lived down the street from me, and of the five kids in that family, there were the twins, Gloria and Gerri (Geraldine). They were (and are) about four years older than me. One of them (Gloria) had a suitor who drove a cool ’60 Chevy convertible, black with a white top, red and white interior, packin’ a hopped-up 348 4-speed.

I first met Jimmy Addison around 1961. The McKay family lived down the street from me, and of the five kids in that family, there were the twins, Gloria and Gerri (Geraldine). They were (and are) about four years older than me. One of them (Gloria) had a suitor who drove a cool ’60 Chevy convertible, black with a white top, red and white interior, packin’ a hopped-up 348 4-speed.

That car was named “Restless”. Jimmy and his friend Ted White raced the car on the street and at the strip and it was very fast for its time, especially with Jimmy behind the wheel. Race driving requires a combination of skill, knowledge, instinct, and a healthy dose of courage, and Jimmy Addison excelled in each of those categories. He was an excellent and meticulous mechanic with amazing driving reflexes, and was quite at home in the driver’s seat at well over 130 miles per hour, on the strip or on the street.

He was born on August 19, 1940, the only child of Archie and Ruth Addison. Born with chronic and life-threatening asthma, Jim was of slight build and frail as a child. But that never held him back. If he wanted to make something happen, he dedicated himself to that task until it was completed; a trait that served him well all through his life.

Now, from the mid-‘50s through the mid-‘60s, the north Woodward suburbs were hotbeds for young rodders with something being built or hopped-up in at least one garage on every block, and, with no shortage of young talented mechanics in Birmingham, Jimmy found himself right in the midst of it all.

One such ‘talented mechanic’ back then was Ted Spehar. Barely old enough to drive, Ted and friend De Nichols rented a garage to work on their cars. The garage was just across Woodward from Jimmy’s house, so it wasn’t long before the like-minded young rodders hooked up and began a lifelong friendship that took them through many ventures and adventures that ultimately led them to unimagined heights in the realms of drag racing and engine building.

In the early ‘60s, Jimmy worked at a local Cadillac dealership and then went to Jerome Oldsmobile in Pontiac, where he bought and built up a ’64 Olds Starfire. It ran a very robust 394-inch motor in a very classy ride. It was also at around this time that Jimmy bought my ’55 Chevy and he and his friend Ted White began converting it into a B/Gasser with 10% engine set-back and all – that is, until a disagreement sent them in separate directions, with White taking his freshly built 327 and going home, leaving Jimmy with a half finished gasser and no motor. The car was sold.

Jimmy first went to work for Ted Spehar in 1965. Ted owned an old Texaco station on Maple a couple blocks west of Adams in Birmingham. Besides accumulating a brisk neighborhood business, Ted had become acquainted with Dick Branstner. I used to see the ’64 Color Me Gone Dodge sitting out in front of the station, along with a little red Dodge pickup with a full-race Hemi protruding through the bed just behind the cab. My first glance at the yet unlettered, carbureted Little Red Wagon, then driven by Jay Howell. It was at this time that Jimmy and Ted began their long affiliation with the Chrysler race program.

In late 1967, Spehar bought a Gulf station on 14 Mile Road just east of Woodward in Birmingham and (I believe) it was at this time, or shortly thereafter, that Jimmy assumed ownership of the now-famous Sunoco station. It was also at about this time that he bought a nasty-looking ’62 Dodge from the Mancini’s.

It was half dark blue and half red primer, and it shook and shuddered and clattered like crazy while in Neutral, but that was nothin’ compared to what it was like in first gear with Addison behind the wheel. I remember, once while we were sitting at a light out on Woodward, I asked Jim, “How the hell do you ever get a race in this thing?” Was it a Hemi? Nope. It was what Ted Spehar described as a “thrashing machine” Stage III 426 Max Wedge in full drag race trim with a manual-shift Torqueflite with a stout set of gears out back!

That car was simply a blast. Talk about an attention-getter! And Jimmy had no problem runnin’ it hard an’ puttin’ it up wet. In comparison with the Bullet, I’d say the Dodge was the vehicular equivalent of the slavering, snarling, unwashed, fairly deranged older brother who lived in the attic. The car was a raging radical handful. It was as though Jimmy was the only one the beast would respond to. Once he was on board, it was safe for you to enter, too. Frankly, I thought the Dodge was a lot more fun than the extremely smooth-running, very streetable and much, much faster critter that was to come next. No one could have predicted the legendary status that Jimmy and his biggest project would achieve.

In the late ‘60s the Sunoco had become a nightly hangout for what was to become Chrysler’s “Direct Connection” gang. An assortment of Chrysler engineers that included Dick Maxwell and Tom Hoover, the man affectionately known as the “Father of the Hemi.” They were there to test speed parts on the street, plain and simple.

Well, one of the cars that were used as rolling test labs was a blue 440-4-barrel powered ’67 Plymouth GTX that was used for drag testing. The car had never been titled. It was snatched right off the back lot, used and abused, and eventually given to Jimmy Addison. The 440 came out, in went a lightened Hemi K-member, followed by a heavily massaged 1968 426 Hemi, the manual-shift tranny, and a Dana 60 rear end with a set of 4.56’s and a pinion snubber for traction.

Well, one of the cars that were used as rolling test labs was a blue 440-4-barrel powered ’67 Plymouth GTX that was used for drag testing. The car had never been titled. It was snatched right off the back lot, used and abused, and eventually given to Jimmy Addison. The 440 came out, in went a lightened Hemi K-member, followed by a heavily massaged 1968 426 Hemi, the manual-shift tranny, and a Dana 60 rear end with a set of 4.56’s and a pinion snubber for traction.

In initial drag tests in ’69 at Motor City Dragway (rented by Terry Cook, then editor of Car Craft Magazine) Jimmy ran a low e.t. of the meet thru-the mufflers 11.89 at 121 mph and an uncapped 11.34 at 127. Not too shabby, eh? Well, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet!

As the weeks went by, Jimmy began making the new car into the quintessential street runner of the day. To make it lighter he took several hundred pounds of weight off the body by using fiberglass body parts and drilling huge holes in anything he could. He then modified the rear wheel wells by slitting them and forcing them outward, in order to fit a wider slick in back. And he worked evenings removing metal (with a hand grinder) from the interior of the Hemi block so the half-inch CSC stroker crank would spin freely, and a set of A990 aluminum heads and a Racer Brown roller cam were added for good measure.

The trick exhaust system was fabricated from three-and-a-half-inch pipe with two runners coming off each header and running through four reworked Cadillac mufflers. The body was then finished and prepped and the car was painted silver.

One day while Terry Cook was at the station, Jimmy took the car out for a little run off the 14 Mile light. As Cook watched Jimmy launch, with virtually no tire smoke, he mentioned that it looked like a silver bullet being fired from a gun. The name stuck, and the legendary team of Jimmy Addison and his Silver Bullet was born.

In January of 1970, I came home on leave from the Navy just before I was to be discharged. I met up with Jim and his then wife Gloria, told them I was looking for a job, and Gloria made Jim hire me. For the next few months, I pumped gas and did oil changes while Jimmy handled the mechanic work.

Now, for those of you who may have come by the station back then, to check out the Bullet or other cars being worked on there, you were probably summarily ordered off the property in a far less than gentle way. Jimmy had a business to run with a lot of time, money and sweat invested there, and he wasn’t about to waste time with kids who came to ogle the race machines. He was not a warm and fuzzy guy when someone seemed to be interfering with him providing for his family.

To Jim, family was everything. And providing the best he could for them was his main goal in life. He once told me that the primary reason he street raced was to supplement the family income. The gruff exterior was a survival tool. But there came a day when I found out what the real Jim Addison was like.

One day a guy brought in his tricked out Dart for an oil change. I did the job, but apparently didn’t tighten the oil drain plug tight and, as the guy drove off, oil began leaking out of the motor at a fairly rapid rate. Thankfully he caught it and came back to the station before he did any internal damage to the motor, and he was pissed!

He began rippin’ on Jimmy and I knew I was as good as dead. When the guy left, with a fresh oil change done by Jimmy, he took me into his office, sat me down…and calmly explained what had happened, what could have happened, and how I had to be extra careful from now on…and he gave me a raise in pay. That was the real Jim Addison. It’s a shame that few people ever knew him like I did.

Well, soon the escapades of Jimmy and the Bullet began being written about in virtually every rodding magazine across the country (and eventually, many different countries) and Jim’s reputation grew and grew, and stories about the undefeated street racer spread far and wide. There was even supposed to be a race set up between Jimmy and Big Willie Robinson, head of the L.A. Street Racers.

Willie drove a Hemi-powered Dodge Daytona. The race was to be somewhere in the Mid-West, half way between here and California, and was being organized by Terry Cook. But nothing ever came of it. Years later, when Jimmy told me the story, he said he’d have won the race anyway because Willie’s car was set up all wrong, the car weighed too much, and the Hemi was an original 426 and fairly mild compared to the Bullet.

Willie drove a Hemi-powered Dodge Daytona. The race was to be somewhere in the Mid-West, half way between here and California, and was being organized by Terry Cook. But nothing ever came of it. Years later, when Jimmy told me the story, he said he’d have won the race anyway because Willie’s car was set up all wrong, the car weighed too much, and the Hemi was an original 426 and fairly mild compared to the Bullet.

Finally, after having done everything he could to the now infamous Silver Bullet, Jimmy sold the car in ’73 or ’74 and began work on the Silver Bullet II, which would have been a Hemi-powered Plymouth Duster. Work was begun on the drive train while the body was being acid dipped, but the car came back with too much damage due to the extreme weakness of the ultra-thin metal, and the project was scrapped.

By the mid-‘70s, with the Arab oil embargo in full swing, the Sunoco station saw less and less performance work and Jimmy sold the station in ’77 or ’78 and he stopped building cars. He continued to work at different gas stations as the Big Three got out of the performance business and, as his asthma worsened, he began to look for a less strenuous line of work. One where he could keep his oxygen bottle close at hand. Eventually, in 1993, he began driving a cab for a living, and found he thoroughly enjoyed the slower pace. He was sitting in his cab in his own driveway when the disease that nearly killed him as a child, tightened it’s grip on him for the last time. He was 65 years old.

Jimmy Addison worked hard all his life and he was fortunate enough to earn a living for most of his life doing what he did best: making engines run better, and often much faster than they had previously done. He was honest and forthright in every way, modest about his successes (which were many), and absolutely devoted to his children, Dawn and Michael, and to his beloved Donna, his wife of eighteen years.

It’s said that people come and go in and out of our lives for a reason. Jimmy Addison gave me a chance that I will always be grateful for. I’ve always been proud of him and I’ve always bragged about his accomplishments, even though he used to get mad at for doing so. And I will be forever proud and honored to have called him friend.

Bill Stinson

If you like the story, let us know. Please leave a comment.

I truely enjoyed the story of Jimmy Addison and the legendary Silver Bullet. Allthough I was too young to drive when I read the stories of Addison during the late 60’s or early 70’s he was my hero. At the time I read all of the performance mags-Hot Rod, Car Craft, Popular Hot Rodding etc. and dreamed of a day when I would have a Mopar muscle car of my own. Eventually I owned a 1969 Plymouth GTX that was my favorite of all the cars I have owned during my life. This evening I noticed tthat on my tv was qualifying for a NHRA racing event in Las Vegas. It has been a very long time since I attended a race or watched it on tv but this all brought back memories of an earlier time and a younger me. I sat at my computer, typed in Jimmy Addison and with a click of the mouse I came to your story. Through the years I wondered about the car and Mr Addison. Thank you for the story and a chance if only for a moment, to bring back wonderfull memories.

I want to say that I loved the article by Bill Stinson. I personally know Bill from when I was younger. Everything Bill said about Jimmy was true. Jim married my twin sister Gloria and I married the guy across the street from Jim, who’s name was Gary. Quite a coincidence. Jim was great with cars and that was his life. He knew them inside and out. The silver bullet was his pride and joy. IT was the fastest car on Woodward Ave. And can be seen at the Woodward Cruise each August along Woodward Ave. from nine mile to eighteen mile road. Quite a stretch to see cars from all over the world to be a part of this one day event. I have been there since the beginning and have seen Jim autograph his t shirts and have pictures taken of him with his fans. Jim was proud and yet humble, Thank you Bill for writing this great tribute about Jim. I’m sure everyone who reads it will appreciate your honesty and caring about your friend Jimmy Addison.

Gerrie (Mckay) Magee

Bill, this is a great story… and thanks for the little blurb on my father, As a kid I used to hang out at Ted’s Texaco when my dad would take his cars there

(Color me Gone, Little Red Wagon).

Bob Branstner

Jimmy was quite a guy! Sorry to hear of his passing. Too many guys from that era have gone and we’re starting to drop like flys. LOL. I have to say that those were “the best of days”. Jay Howell

Go Jimmy, go!

Great story,great tribute to legend. I was a senior in high school when I first saw the Silver Bullet. Jimmy trailered it down to Toledo to race a friend of mine who is no longer with us either. The car Paul Kneer drove was a 59 Corvette tha belonged to Carl Norton. It was also a 10second car on the strip,ran at Norwalk, but would street race for good money. Jimmy showed up at the A&P parking lot on Main St.in East Toledo,I remember the bulged out qtr.panels,the car was trick for the era. The took off out to the county in Oregon Oh.to get it on,with a caravan of cars following them,(nothing suspicious looking here),but everywhere they went the cops showed up before it could take place. They even tried going to West Toledo,and up to lower Michigan,but same thing cops everywhere. To bad they never got the chance to race,their et’s were real close,would have been a great race. Paul had a lot of guts,and could really pound a 4-speed,that Vette used to leave super hard w/wheels in air,never had 60 ft.times back then,don’t know if he could have stayed out in front of that big Hemi though,. Those cubic inches are known to reel you in in the big end. Paul never forgot that knight,nor did I,Jimmy was really down to earth and a great guy,you could tell there was a mutual respect for each other that night. The Vette was still in primer,not near as pretty as the Bullet was,but I remenber Jimmy telling Paul pretty don’t make it fast,and that a small block home built that is as fast as your car goes is nothin to be hangin your head about. Hard living took Paul from us,but I never will forget that night when those to met. Maybe It was a good thing the never got to race,because Paul never lost a street race with that old Vette,and from what I,ve been told Jimmy never did either. As the writer of the article Banging The Gears in the Googuys writes “That’s the way I remember it”. Kirk Aldrich,Genoa Oh.

Great story, thanks for letting me relive some of my past memories.

I grew up on Woodard Ave in the late 60’s, I remember the Silver Bullet and the Sunoco station; they were famous to all us Mopar lover’s back then. We used to have Jimmy curve our distrubutor’s back then and it was an honor to be at the station (not to mention the thrill).

The present owner of the Silver Bullet is a friend of mine and he took me for a brief ride in the car, a thrill to just drive over to the trailer and help lower the hood on the famous Bullet.

Those days/nights on Woodard were some of the best times of my life, an era that will never ever exist again.

Thanks for honoring both legends, Jimmy and the Bullet.

Browney Mascow

Boyne City, Mi.

A Mopar Collector

Very interesting article but your introduction needs work. Accuracy is important when dealing with the history of our sport. The Silver Bullet is not a ’68. You should change this for the benifit of those readers who are not familiar with this famous car.

Dave Lentz

Dave, looks like your’re right. I’m changing the story. “For the benefit of readers” can you say how to tell the difference between a 67 and 68? Plymouth’s aren’t my thing.

-pikesan

The intermediate sized Plymouth ( Belvedere, Satellite, GTX, etc. ) carried the performance banner for Mopar from 1965 to the early 70’s. The 1966 and 1967 models ( the first to have the 426 Street Hemi ) have the same very angular body style. The 1968, 1969, and 1970 had an entirely different body which was more rounded in design. The best known of this style is the Roadrunner. Photos can be found on Google Images and other internet sources. I hope this helps answer your question.

Dave Lentz

He was a good guy. He ran hard too. He was the guy that convinced me to switch to roller cams in my hemis. Back then nobody used them, everyone was scared of them because of how high-tech (and pricey) they were. He knew to run really deep gears in the hemis so you could leave hard and fast and eliminate the smoke show in favor of an awesome launch. I think his gears were steeper than 4.56’s, I know mine were and his launched too well to be below the 5’s. He passed on a lot of good tricks to us hemi guys and he had some connections with regards to cutting edge parts that meant if you knew Jimmy you had a front row seat in the muscle car wars.

RIP Jimmy, I know you were ill way too long…you’re in a better place now.

I am like a kid again everytime I get near THE BULLET. This Saturday at Woodward,I met Harold Sullivan and talked with him as if we knew each other for a long time. My grandson ,Kevin, was invited to sit in the car ! The grin in the pictures is PRICELESS. The car, history, and lore will live on forever. I truly cannot think of any other story or car that brings on a magical feeling like the BULLET! Jimmy and the Bullet paved the way by setting the bar high , and striving to achieve your goals. The best……simply the best

well, thanks for writing this Bill. it brought back lots of memories. I worked nights at the Sunoco Performance Automotive for Jimmy as a summer job from 1970-73. Jimmy was just the way you described…

Paul Schramm also worked there at the same time, and we built matching ’64 Plymouths with 440 6 packs while pumping gas and polishing parts late at night. We had some great summers working for Jimmy. You never knew who was going to roll in with what.

We learned a lot, all the cars we built were quiet, daily drivers, that scorched Woodward and I-96. Everything was done the right way, (or it was done over until it was right). That was Jimmy…

I just read your post Richard, please contact me @ moc.oohaynull@885repivimeh I own Jimmy’s Duster that he never completed…I would like to restore it to the way he would have built it…I am looking for information regarding who the original builder was etc. Thanks, Bill Adams

Bill, I will forward your comment to Richard to make sure he gets it. Please make sure MyRideisMe.com has the story when you start working on it. I’d love to see it as-is too. Please mail moc.emsiedirymnull@nimda. Thanks!

This brought back many good memories from 1968.I met Ted and Jimmie when they built the motor for our 1968 Plymouth GTX SS/FA car which we raced out of Dan O’Shaughnessey Chrysler-Plymouth in Lansing MI. Little did I realize back then , we were all becoming a part of drag racing history. I think the best part of all of this is, I still love Drag Racing ,Mopars and our old GTX Superstock sits in a drive way about a mile away from my house today.

hi! don’t know if this is still very active but i had to write & say what a great story this is! i grew up in the u.p. of michigan so i never saw any action on woodward, although my good friend brian from high school wrecked his 1965 389 4 speed gto racing on woodward! my brother owned a 1966 metallic green plymouth satellite that was a blast to drive even with the 318. he later bought a 1971 demon 340 that i took over payments on when i got back from vietnam. had a ball in that one too even though i wrecked it twice in one year, hot rods aren’t too good to drive in the u.p. in the winter! so as you may have guessed i have a little mopar in my blood & jimmys’ story has always been fascinating to me. thank you for a glimpse of the past. i live in minneapolis now but the woodward cruise is definitely on my bucket list…..

I am a Mopar owner and enthusiast and I enjoyed the story. What I like about high performance Mopars is there are so many cool stories about the cars and very interesting people associated with them.

What a nice story about Jimmy and the Silver Bullet, In the late 60’s I spent alot of my time at Detroit Dragway not on Woodward. I today spend alot of time at the Dream cruise every year and I have a Pro street Mustang which I take to Woodward. Thanks for sharing your story. The Silver Bullet today is still one of my favorites. Larry.

Bill, my name is Jim Weber everybody called me Web , I was Jimmy’s mechanic for a number of years at the sunoco station on woodward. I started working with Jimmy when he work for Ted Spehar at the gulf station on 14 mile rd. I am now retired and liviing in Sarasota, fla. A friend of mine told me about the site My ride is me and I came upon the article you wrote. I was saddened about Jimmy’s death he was not only my boss at one time he was a great guy and a good friend. I want to thank you for writing a great article about your friend and mine. Thanks so very much. Yours truly, Jim Weber

Jim, Please contact me @ moc.oohaynull@885repivimeh . I have some questions regarding Jimmy’s Silver Bullet II Duster. Thanks, Bill

I remember racing the Silver Bullet off the light at 12 and Woodward in my 1965 GTO. I was 18 years old in 1971 and just graduated high school. I certainly had no idea what the Bullet was, but he left me like I was tied to a post.

Fond memories of those days.

Thanks Layne! We’ve received so many great comments from the Silver Bullet stories! – pikesan

My Great uncle raced a few times up on woodward in a orange 68 Hemi Cornet R/T he saw the Bullet and Jimmy but never wanted to race him. He has past away, but the car still in the family(his grandson who was in 3th grade when he died got the car wiled to him) wanting restorations in a barn down the road from me. The car has tire swirls down the side from a Torino he raced that the rear end blow apart if you know of the car he beat the crap out of it. Me and my dad have a black 67 Plymouth Belvedere that we had a 500 inch stroker kit 440 in but were taking it down to go black with red interior and putting in a 383 4 speed, and we just got a 67 Belvedere convertible that where starting on, plus are other 68 Road Runner and more. The Bullet was a big driving force for my dad growing up in his grandpas shop reading about the Bullet.

Awesome story Bill & I concur about Jimmy, he & Web worked on my 67 Barracuda back in 72 off & on, Both great guys, I remember talkin & learnin more stuff from those guys. Web, if you happen to see this, a big hello. I hope you’re well!! I remember your 64 Polara was no slouch either. I remember when, well you remember the acetylene cannon I won’t go any further….Jimmy is truly a legend & a fine person, I knew his gruff attitude, but that was Jim, under it all he was a fine father & hubby & one helluva car man!! I was saddened when we lost his presence here on earth….I will never forget the fine memories @ Performance Auto, I too remember the acid dipped Duster they decided not to build….Happy Trails, thanx for the memories!!

Many Thanks to Bill Stinson for sharing his story about Jimmy Addison and the Silver Bullet GTX. Some of you reading this post may recognize my name (Steve Magnante) as one of the on-stage Barrett-Jackson vehicle commentators on TV or from my 20 years of writing for car magazines like HOT ROD, CAR CRAFT, MOPAR ACTION, etc. I am 50 years old and thus too young to have lived the Supercar Sixties first hand. BUT…like a lot of current muscle car fanatics, I’m trying my best to make up for lost time! In 1996 I was a freelance writer for Mopar Action magazine when editor Cliff Gromer asked me to write the words for a feature story on the restored Silver Bullet. I was fully aware of the legend and lore of the car – part of my vintage magazine collection includes well worn copies of the September 1971 issue of Car Craft and the Spring 1972 issue of 1001 Custom & Rod Ideas – both with great feature stories on the Silver Bullet. Gromer gave me Jim Addison’s home phone number and I excitedly called him for some background on his life with the car. I was struck by Jim’s humility but could read between the lines and know he must have been one heck of a fighter at the height of his powers back in the day. I must admit one error. I incorrectly stated that Ro McGonegal was the one who conjured the “Silver Bullet” name. Not only does Stinson’s story tell the true story that Terry Cook assigned the name, but Ro McGonegal himself corrected me in 1998 when he became my boss at Hot Rod magazine during my 7 year stint there as Technical Editor. I still have a cassette tape recording of that 35 minute 1996 interview I conducted with Jimmy Addison. Sadly, much of the nitty-gritty details of the Woodward Ave. street racing scene were “scrubbed clean” by an overzealous Mopar Action magazine copy editor who was afraid Jim’s accounts might jeopardize the magazine’s trademark use agreement with Chrysler – which frowned on discussion of illegal driving behavior. That fellow has since been sent to the “gallows”, but my story was sadly “de-fanged” in the process and I apologize to anybody who felt short changed by the sanitized version that appeared in the October 1996 issue of Mopar Action. I never did hear back from Jimmy after I sent him copies of the finished magazine story but hope he didn’t think I was the one that censored his exciting stories. Lets all make it a point to gather these guys NOW and hear their stories before they are gone. Rest in peace Jimmy Addison, your legend lives on! -Steve Magnante

My Silver Bullet story Toledo, OH 1971

Addison showed up at “The Secor Hut”…….the White Hut drive-in

on Secor Road.

The detailed Bullet was on an immaculate black Bock Dragstar open

trailer being pulled by a equally pristine black Dodge shortbed stepside pickup……the whole outfit rolling on chrome Cragar S/S wheels.

With the car setting there on the trailer I had a close-up view of that

magnificient exhaust system. Those four 500 cu in Cadillac mufflers

were much larger than the modern “Flow-master” sized renditions would

have you believe.

Several other (4?) trailered outfits had followed him down from Detroit

hoping for some side action.

My friend Trigger’s dark green ’69 Camaro had a tunnel-rammed open-

chamber aluminum headed Rat motor and had, in fact, ran low tens in

NHRA modified eliminator at Indy the previous year. With it’s “Grump

Lump” hood scoop it looked like Wally Booth’s car in a darker shade of

green. It had a 3″ exhaust sustem all the way back to behind and under

the rear end allowing some occasional street driving but tonight, it too

was on a trailer.

They jawed for hours and then the whole entourage, with at least a

hundred “spectators” in tow, moved towards a 2-lane country road in southern Michigan.

It was after midnight when we pulled into the stone parking lot of a small

church. The pastor’s house showed a hundred yards away under a single

bulb on a telephone pole in the yard. The assembled multitudes had

stopped on the shallow grass ditches at both sides of the road and were

waiting quietly in anticipation.

As those of us in the tow vehicles finally moved in unison to lower the

ramps and unchain the cars the loud “chop-chop-chop” sound of a police

helicopter rapidly approached with a spotlight scanning back and forth on

the ground. At the same time, all of the lights in the house came on. The

spectator’s cars roared to life and scatterred like church mice. We threw

our ramps in the back of the pickups and left immediately.

Back in Toledo we went to a Sunoco station on the old East Side that was

closed. The manager was in our group and unlocked the doors. There was

talk of arranging another attempt on another night. By now it was 2:00 AM.

As the core group huddled and talked in the office, there was a deep rumble

outside. We were surprised as a fully uniformed Toledo police officer stepped

from a year-old Superbird. It became apparent that all of these guys knew

each other when he asked who won. He expressed disappointment after

learning that the race never went off.

He got into his Superbird and pulled into the street. He let out a big laugh

and yelled “Anybody want to go for top end”? Then he did a huge burnout

and smoked his way into the night.

We all made our ways home as the night turned to day. I didn’t see Jimmy

Addison again until we took our Hemi Duster to Carlisle in 1997. He was there

with Harold Sullivan, and the Silver Bullet.

Now he’s gone.

Hey, Craig, Hope all’s well! I’m a bit slow on the up-take and didn’t see these comments here till tonight, October 23, 2014! Sorry!

I have a question: Did I mention in the piece that the ‘Bullet was a ’68? If so, it was a typo, as I have known for nearly 45 years, that the car was a ’67. It somehow escaped my attention during the proof-reading process, for which I apologize.

Neat to read the comments, especially that from Gerri McGee (Jim’s one-time sister-in-law). She and Gloria were very kind to me when’ in my early teens, I got into cars, but moreover, into the music of the day…and the twins had every new 45 rpm record the minute it hit Marty’s Records up in town, and we used to sit on the living room floor and play the records all afternoon during the summer! It was them that I credit for my great love of late-’50s through mid-’60s Rock ‘n’ Roll!!!

Anyway, thanks for providing the forum for me and others to remember an extraordinary race driver/mechanic, whose creation is still very much talked and written about to this day, and thanks for the opportunity to let everyone know what the ‘real’ Jim Addison was like. He was a good man.

I want to know if I am the only one who whole heartedly comes to tears when reading Jimmy’s life story, and what the impact of the images of him standing beside that silver GTX invokes? Thanks Jimmy for the inspiration and for what you left behind. It’s guys like ALL of us, that only dream of what it must have been like.. Rest in Peace.

Yours Truly.

Dave

This article was quite a flashback for me. My brother Jerry and I used to buy all our gas and get our “not so stock” cars worked on at Jimmy’s Sunoco. We were just a couple of nighty cruisers/ racers on Woodward. Many fond memories back then. We knew our cars were fast , but never imagined we would be part of muscle car history. I drove a 69 black Dart Swinger and my brother drove a 65 L79 gold Chevelle Malibu SS. RIP Jimmy.

All i can say is WOW he was a great Mopar man & Family man he lived & raced in the Glory days that car has always been my most Favorite car of all time one day i will see it in person..

I was born in ’63. I had an uncle who was born in ’49, and had told me some of his street racing stories from the 60’s. We lived a 1/2 mile from Woodward and 11 mile. My uncle had the Car Craft issue with Jimmy’s silver Bullet on it, from ’71 I believe, and had told me about Jimmy Addison and the Silver Bullet. I don’t think they were friends per se, as my uncle was a bit younger than him, but he respected his accomplishments and abilities.

A few years later in ’82, I was 19 and working at one of my first jobs as a tire buster and oil change guy at a Goodyear franchise. Then they hired a new old guy that worked at the other end of the 8 bay shop. It was Jimmy Addison. And I was the only one in the shop who knew who he was. But I had Asperger’s and was very introverted, and never had the courage to go talk to him at the other end of the shop. And I couldn’t believe no one else older than me recognized him or knew of his legend. I think we only worked at the same place for a month or two before I got fired for coming in late on a Saturday(a big no-no at a tire store) because I was banging my new girlfriend instead of going to work. But I never forgot getting to work with the great street racer Jimmy Addison.

Tom